The current crisis in Syria is one which demands our attention and one which, sadly, reminds us of our war weariness. We know what images to expect: photos of people lying dead in a street, videos of bombs wasting buildings. We expect them because we, as a species, and for want of a better word, like them.

Race car drivers are skilled at taking corners, driving fast, holding the car on the track – some even run marathons to stay in shape. But fans come for the crashes. Those burst-into-flames, fear-inducing moments of horror: the injuries, the smashing of cars. This is what the fans crave. In ice hockey it is not so much the skill on skates or stick handling that the fans come to see, but, rather, the fist fights. In football, head injuries occur and yet fans love the tackling. We — and not just the ‘we’ of the united states, we — worldwide bystanders to action — love to see flames, blood and terror. It is also true of the news. We see war, violence, murder, and grim photographs of mourning mothers and outraged fathers, as news . We see photographs of bombed out cities and people running in fear, and we think that is all there is to the story. But there is so much more.

“VII” is one of the world’s preeminent photo agencies. Its director, Stephen Mayes, is attempting to lead photojournalism in the direction of that ‘so much more.’ Here is Mayes, speaking to the French magazine 6Mois, The 21st Century in Pictures:

‘The representations of war are bound up in stereotypes. Certain visual codes regularly recur. They show us what we already know, instead of attempting to open up new horizons,’ he says, denouncing the standardisation of images. He suggests that photojournalists tell other stories, ones that are closer to daily life or the economic world.

Even in war-torn communities, people struggle to earn a living, educate their children, build shelters, purify water. They are also struggling to raise white flags and talk at a table. There are new businesses starting, and history is being made in places other than battlefields. There are important stories to be told far away from the bloodshed:

From 6Mois:

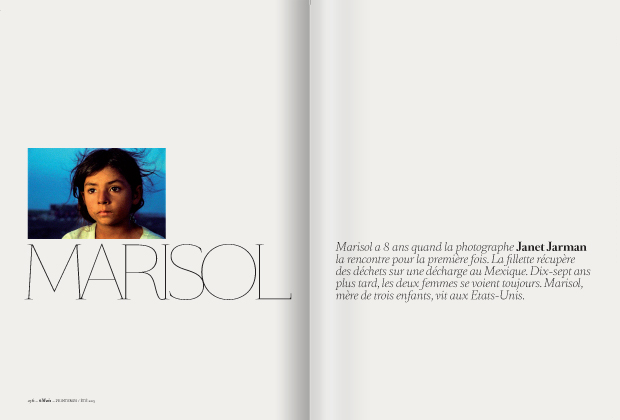

‘Marisol was 8 when photographer Janet Jarman met her for the first time. The little girl was recycling refuse at a dump in Mexico. Seventeen years later, the two women still meet. Marisol, a mother of three children, lives in the United States.’

A long term photo story looks at who makes war, who is affected by war, who is trying to mend the wounds of war, but as with ‘Marisol,’ it can also offer so many other ways to look at the world besides the killing, besides the same horror-stricken faces of the victims and their families. Stephen Mayes of “VII“ is asking some great questions here, and in its commitment to publishing these other stories, and 6Mois is trying to answer them.